In our contemporary U.S. American society and culture, the name “Mennonite” often causes a strange reaction: a wrinkled nose, a hard-focusing brow, a cautious gaze, and the question, “Is that like an Amish person? Do you ride buggies?” While there are many types of Mennonites, churches like South Union are no longer distinguished from the society at large by dress, or by technology preferences, or by cultural/ethnic traditions, but are a people marked by a particular way of looking at Scripture and following Jesus. If you were to walk into our church on a given Sunday morning, it would look very much like other churches – some people are dressed in suits and dresses, others in jeans and a flannel shirt or t-shirt. Most people have cellphones, and no one has a horse parked out front.

So, what exactly makes a “Mennonite?” Historically, there are certain cultural and ethnic traditions that are associated with Mennonites, but these are slowly falling away to become more inclusive to those not raised Mennonite. The easiest way to describe Mennonites is to simply say that we call ourselves by the name of someone whose leadership and theology had a profound impact on the beginning of the Mennonite Christian movement. For example, “Lutherans” are called Lutherans because they plant themselves firmly in Martin Luther’s shadow, i.e. his way of seeing Scripture and doing church. Calvinists likewise plant themselves firmly in the shadow of John Calvin. Mennonites plant themselves in the shadow of Menno Simmons, a leader and theologian who entered the Anabaptist movement in one of its earlier stages. He helped shape and frame the beliefs and way of being church for early Anabaptists.

I hear you asking, “Wait what? What’s an Anabaptist?” During the Reformation (the time period where Luther hammered his 95 Theses to reform the Catholic Church and who was one of the translators to make the Bible accessible to the everyday person thanks to the printing press) the Anabaptists were those folks who read the Bible and said, “Whoa! We are not following Jesus as closely as we should! Look at what is in the sermon on the mount! Look what the Great Commission says! We must do this!”

In response, the Anabaptists began to follow Jesus very seriously, agreeing with Luther that people were “saved by grace through faith,” but also that a transformed life (one that looks more like Jesus everyday) should be the result of salvation. This led the Anabaptists on a path of establishing a new community, of being “re-baptized” to show their committed choice to Christ as adults (instead of just as babies), and of being devoted to following Jesus’ teachings as closely as possible. One serious claim is “Jesus is Lord and Savior,” which means our first allegiance is always exclusively to Jesus over against government, city, nation, tribe, family, etc.

However, being caught in a disagreement between two institutions that at the time had no problem using government and violence to enforce their views (Catholicism and Reformers), led to a great deal of persecution for the mainly pacifist movement. Mutated versions of Anabaptism did not help, such as the very violent rebellion in the German city of Münster, headed by radical “Anabaptists.” This rebellion allowed leaders to paint the Anabaptists as dangerous and violent heretics in need of extermination, whether by renouncing their Anabaptist ways or by execution. Yet, the true Anabaptist movement survived and grew.

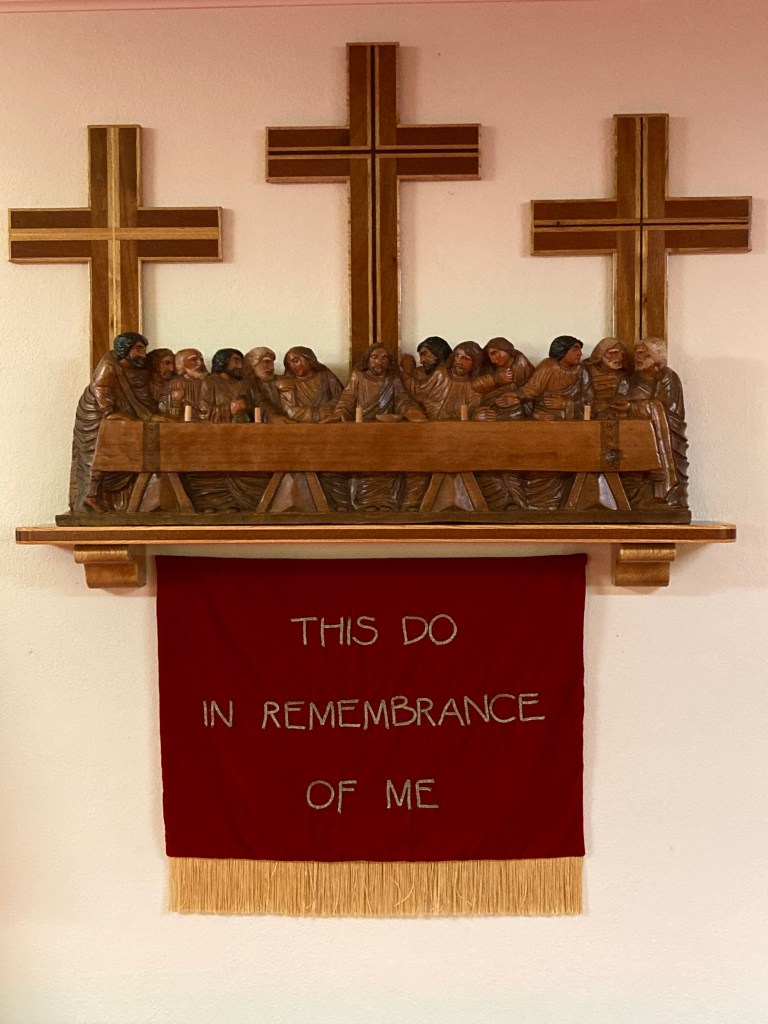

In summary, Mennonites are the heirs of one stream of Anabaptism led by Menno Simmons. While we no longer have the strict cultural and ethnic traditions binding us, we still take very seriously the teachings of Jesus Christ, the Bible, and our role as a community, that is to say, the church. We take seriously the authority of Scripture, the Lord’s supper, believer’s baptism, the call to love our enemies (nonviolent resistance), the practice of foot-washing, being the church, and following Jesus in daily life.